Small-scale dairy farming plays a critical role in food security, rural livelihoods, and nutritional improvement in many developing economies. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the dairy sector is predominantly smallholder-based; however, productivity remains persistently low due to limited adoption of modern dairy production technologies and inadequate access to support services. In Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, small-scale dairy farmers continue to experience low milk yields per cow and per household, threatening household incomes, food security, and the sustainability of the local dairy value chain. Identifying context-specific technological constraints is therefore essential for designing effective policy and extension interventions. This study examined the technological factors influencing dairy cow milk production among 196 small-scale dairy farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County. A cross-sectional survey design was employed, and primary data were collected using structured questionnaires administered to farm households. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to assess the level of adoption of dairy production technologies and multiple linear regression to estimate the effects of selected technological variables on milk production. The results revealed generally low adoption of key dairy technologies. Only 42.9% of farmers used artificial insemination, 28% accessed deworming services, 26% accessed vaccination services, 17.3% adopted high-yielding fodder and pasture, and 21.4% kept improved dairy breeds. Average annual milk production per household was 2,925 liters, while average milk production per cow was 975 liters per year, equivalent to 4.5 liters per cow per day, values that are substantially below the national benchmark of approximately 10 liters per cow per day. Multiple linear regression analysis indicated that use of artificial insemination, access to deworming services, adoption of high-yielding fodder and pasture, access to improved feeds such as hay and silage, and adoption of improved dairy breeds had positive and statistically significant effects on milk production. Other technologies, including mechanized milking, milk cooling facilities, and digital platforms, did not show significant effects, largely due to their very low adoption levels among farmers. The findings demonstrate that technological adoption is a critical determinant of milk productivity among small-scale dairy farmers. Addressing existing technological gaps through affordable breeding services, improved animal health management, enhanced feed systems, and strengthened extension support is essential for increasing milk production, improving household incomes, and contributing to Kenya’s broader food security and agricultural transformation goals.

| Published in | International Journal of Agricultural Economics (Volume 11, Issue 1) |

| DOI | 10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11 |

| Page(s) | 1-15 |

| Creative Commons |

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. |

| Copyright |

Copyright © The Author(s), 2026. Published by Science Publishing Group |

Technological Factors, Small-Scale Dairy Farmers, Livestock, Cow Milk Production, Marakwet East Sub-County, Kenya

S. No | Ward | Target Population |

|---|---|---|

1 | Kapyego | 2,108 |

2 | Sambirir | 1,419 |

3 | Endo | 2,028 |

4 | Embobut | 2,809 |

Total | 8,364 | |

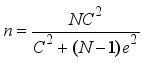

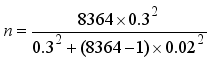

(1)

(1)  (2)

(2) Ward | Target Population | Proportion (Percent) | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

Kapyego | 2,108 | 25.2% | 55 |

Sambirir | 1,419 | 17.0% | 38 |

Endo | 2,028 | 24.2% | 53 |

Embobut | 2,809 | 33.6% | 74 |

Total | 8,364 | 100% | 220 |

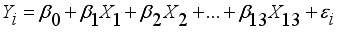

(3)

(3) Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Age of the household heads (Years) | 47 | 8.1 | 28 | 60 |

Family size (Number) | 5.0 | 2.0 | 3 | 10 |

Farmer experience (Years) | 16.8 | 8.1 | 3 | 30 |

Total farm income (USD)† | 900 | 250 | 100 | 2000 |

Variable | Frequency (n=196) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

Gender | ||

Male | 129 | 65.8 |

Female | 67 | 34.2 |

Marital status | ||

Single | 7 | 3.6 |

Married | 177 | 90.3 |

Widowed shown | 12 | 6.1 |

Level of education | ||

Primary | 104 | 53.1 |

Secondary | 83 | 42.3 |

College | 9 | 4.6 |

Farmer occupation | ||

Full-time farmer | 124 | 63.3 |

Part-time farmer | 18 | 9.2 |

Fully employed | 42 | 21.4 |

Trader | 12 | 6.1 |

Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

Use of Artificial Insemination | ||

Yes | 84 | 42.9 |

No | 112 | 57.1 |

Access to vaccination services | ||

Yes | 51 | 26.0 |

No | 145 | 74.0 |

Access to deworming services | ||

Yes | 55 | 28.0 |

No | 141 | 72.0 |

Access to curative services | ||

Yes | 43 | 21.9 |

No | 153 | 78.1 |

Having milking machines | ||

Yes | 4 | 2.0 |

No | 192 | 98.0 |

Access to milk cooling facilities | ||

Yes | 14 | 7.1 |

No | 182 | 92.9 |

Adopted high-yielding fodder/pasture | ||

Yes | 34 | 17.3 |

No | 162 | 82.7 |

Access to feed chopping/milling technology | ||

Yes | 11 | 5.6 |

No | 185 | 94.4 |

Access to improved feeds | ||

Yes | 61 | 31.1 |

No | 135 | 68.9 |

Adopted improved dairy breeds | ||

Yes | 42 | 21.4 |

No | 154 | 78.6 |

Access to communication services | ||

Yes | 40 | 20.4 |

No | 156 | 79.6 |

Access to a digital platform | ||

Yes | 11 | 5.6 |

No | 185 | 94.4 |

Access to pregnancy diagnosis technology | ||

Yes | 19 | 9.7 |

No | 177 | 90.3 |

Milk production (litres) | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|

Average annual milk production per household | 2,925 | 211 |

Average annual milk production per cow | 975 | 101 |

Average daily milk production per cow | 4.5 | 0.4 |

Variables | Multicollinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|

Tolerance | VIF | |

Access to Artificial Insemination | 0.690 | 1.450 |

Access to vaccination services | 0.789 | 1.267 |

Access to deworming services | 0.935 | 1.070 |

Access to curative services | 0.729 | 1.372 |

Access to milking facility | 0.755 | 1.325 |

Access to milk cooling facilities | 0.674 | 1.483 |

Adopted high-yielding fodder/pasture | 0.705 | 1.419 |

Access to feed milling technology | 0.766 | 1.305 |

Access to improved feeds | 0.738 | 1.356 |

Adopted improved dairy breeds | 0.695 | 1.438 |

Access to communication services | 0.700 | 1.428 |

Access to a digital platform | 0.626 | 1.598 |

Access to pregnancy diagnosis technology | 0.508 | 1.967 |

Regression Statistics | |||||

Model summary | |||||

Multiple R | 0.857 | ||||

R Square | 0.733 | ||||

Adjusted R Square | 0.715 | ||||

Observations | 196 | ||||

Standard Error | 1.266 | ||||

ANOVA | SS | df | MS | F | P-value |

Regression | 805.805 | 13 | 61.985 | 38.661 | <0.001 |

Residual | 291.803 | 182 | 1.603 | ||

Total | 1097.608 | 195 | |||

Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t Stat | P-value | ||

Beta | Std. Error | Beta | |||

2.222 | 0.149 | 14.934 | 0.000 | ||

Use of Artificial Insemination | 0.690 | 0.220 | 0.144 | 3.137 | 0.002** |

Access to vaccination services | -0.046 | 0.232 | -0.009 | -0.200 | 0.842 |

Access to deworming services | 0.684 | 0.208 | 0.130 | 3.285 | 0.001** |

Access to curative services | 0.459 | 0.256 | 0.080 | 1.793 | 0.075 |

Access to milking machines | -0.428 | 0.736 | -0.026 | -0.581 | 0.562 |

Access to milk cooling machine | 0.757 | 0.428 | 0.082 | 1.770 | 0.078 |

Adoption of high yielding fodder/pasture | 1.834 | 0.285 | 0.294 | 6.448 | 0.000*** |

Access to feed milling technology | 0.272 | 0.449 | 0.026 | 0.607 | 0.545 |

Access to improved feeds | 1.780 | 0.227 | 0.348 | 7.827 | 0.000*** |

Adoption of improved dairy breeds | 1.672 | 0.264 | 0.290 | 6.324 | 0.000*** |

Access to communication services | -0.071 | 0.268 | -0.012 | -0.263 | 0.793 |

Access to digital platform | 0.687 | 0.497 | 0.067 | 1.383 | 0.168 |

Access to pregnancy diagnosis services | 0.502 | 0.429 | 0.063 | 1.170 | 0.243 |

MMT | Million metric tonnes |

AI | Artificial Insemination |

VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

ECM | Energy Corrected Milk |

| [1] | Radwan, H., H. El Qaliouby, and E. A. Elfadl, Classification and prediction of milk yield level for Holstein Friesian cattle using parametric and non-parametric statistical classification models. Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research, 2020. 7(3): 429. |

| [2] | Miller, L. C., S. Neupane, N. Joshi, M. Lohani, K. Sah, and B. Shrestha, Dairy animal ownership and household milk production associated with better child and family diet in rural Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients, 2022. 14(10): 2074. |

| [3] | Smith, N. W., A. J. Fletcher, J. P. Hill, and W. C. McNabb, Modeling the contribution of milk to global nutrition. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2022. 8: 1287. |

| [4] | FAO. Dairy Market Review 2022. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022. |

| [5] | Taramuel-Taramuel, F., et al. Adoption of integrated dairy production technologies and impact on milk yield. Livestock Science, 2025. 275: 105312. |

| [6] | Akzar, H., et al. Technological adoption and profitability in small-scale dairy systems: Evidence from South Asia. Agricultural Systems, 2023. 206: 103645. |

| [7] | Kassa, S., et al. Technological gaps in small-scale dairying in East Africa. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2020. 52(5): 2529-2538. |

| [8] | Ayuko, B., et al. Feed and breeding technology adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa: Determinants and impact. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2023. 18(3): 134-144. |

| [9] | Korir, H., et al. Adoption and constraints of dairy innovations among Kenyan small-scale. Journal of Dairy Science, 2023. 106(2): 1156-1167. |

| [10] | Ngeno, K., et al. Technological innovation and performance of small-scale dairies in Kenya. Heliyon, 2024. 10(2): e22234. |

| [11] | Kirimi, L., et al. Patterns of technology clustering and productivity among small-scale dairy farmers in Kenya. Agricultural Economics, 2024. 55(1): 45-59. |

| [12] | Chelang’a, R., et al. Determinants of integrated technology adoption in small-scale dairy systems in East Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2025. 9: 117983. |

| [13] | Kogo, B. Adoption of silage technology among small-scale dairy farmers in Kenya. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal, 2024. 88(1): 34-42. |

| [14] | Gichuki, S. & Wambu, C. Fodder conservation and dairy productivity among Kenyan highland farmers. Tropical Grasslands, 2024. 12: 12-25. |

| [15] | Mutuma, J. Digital extension and technology adoption among small-scale dairy farmers in Kenya. ICT in Agriculture Journal, 2023. 6(2): 67-78. |

| [16] | MoALFC. Kenya Dairy Sector Annual Report 2021. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives, 2021. |

| [17] | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Overview of the Kenya Dairy Industry. Nairobi: USDA GAIN Report KE2024-0013, 2024. |

| [18] | Majok, D. A. Factors influencing adoption of artificial insemination by small-scale livestock farmers in dryland production systems of Kenya. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Nairobi, 2020. |

| [19] | Livestock Kenya. The impact of liberalization of Artificial Insemination services in Kenya. Livestock Kenya Knowledgebase, 2017. |

| [20] | Ministry of Agriculture & Livestock Development (MoALD). Kenya to vaccinate 22 million animals in nationwide campaign. Nairobi: Government of Kenya, 2024. |

| [21] | Feed & Fodder Kenya. Emerging technologies in dairy farming: Revolutionizing the future of Kenyan dairy industry. Feed & Fodder Kenya, 2023. |

| [22] | Ngongo, C. O. Analysis of factors affecting adoption of ICT solutions in dairy farming cooperative societies in Meru County. M.Sc. Thesis, Strathmore University, 2019. |

| [23] | AVSI Foundation. Maziwa (milk) - Empowerment of dairy cooperatives in Meru County, Kenya: Final Evaluation Report. AVSI Reports, 2021. |

| [24] | Elgeyo-Marakwet County Government. Improvement of dairy sector. County Government of Elgeyo-Marakwet Publications, 2023. |

| [25] | Kenya News Agency. Elgeyo Marakwet distributes heifers to boost milk production. Kenya News Agency, November 8, 2023. |

| [26] | Mwai, O. A., V. Tsuma, J. O. Owino, L. Ochieng, and E. J. O. Rao. Accelerating genetic improvement in emerging small-scale dairy systems through fixed-time and conventional artificial insemination technologies: Experiences from Kenya. ILRI Publications, Nairobi, 2020. |

| [27] | Kogo, T. K. Assessment of fodder conservation in small-scale dairy farming systems in highland and midlands of eastern Kenya. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Embu, 2023. |

| [28] | Munene, G. The Digital Dairy Farm: DigiCow delivers free livestock management for small-scale farmers. FarmBiz Africa, January 31, 2023. |

| [29] | Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census: Volume II. Nairobi: KNBS, 2019. |

| [30] | Jaetzold, R., Schmidt, H., Hornetz, B., & Shisanya, C. Farm Management Handbook of Kenya Vol. II: Natural Conditions and Farm Management Information. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture, 2012. |

| [31] | Place, F., & Kariuki, G. Land tenure and agricultural productivity in Kenya. Journal of Development Studies, 2020. 56(6): 1105-1121. |

| [32] | Musyoka, M. P., et al. Fruit production and marketing in Kenya: Trends and prospects. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2021. 16(4): 567-578. |

| [33] | Kothari, C. R. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. 4th ed. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers, 2019. |

| [34] | Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2018. |

| [35] | Elgeyo-Marakwet County Government. Livestock and Fisheries Annual Report 2022. Iten: County Government of Elgeyo-Marakwet, 2022. |

| [36] | Nassiuma, D. K. Survey sampling: Theory and methods. International Journal of Applied Statistics, 2000. 1(1): 1-17. |

| [37] | Orodho, J. A. Sampling techniques in educational and social science research. Kenya Journal of Education Studies, 2017. 12(2): 45-56. |

| [38] | Mugenda, O. M., & Mugenda, A. G. Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Nairobi: Acts Press, 2003. |

| [39] | Bryman, A. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. |

| [40] | Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2011. 2: 53-55. |

| [41] | Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 5th ed. London: Sage Publications, 2018. |

| [42] | Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. Basic Econometrics. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. |

| [43] | Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis. 8th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2019. |

| [44] | O’Brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 2007. 41(5): 673-690. |

| [45] | Babbie, E. R. The Practice of Social Research. 15th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2021. |

| [46] | Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. |

| [47] | Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022. Nairobi: KNBS, 2022. |

| [48] | World Bank. Kenya Rural Population Trends. Washington, DC: World Bank Data, 2021. for migration and rural population structure. |

| [49] | FAO. Household Structures and Family Labor in Rural Kenya. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2020. |

| [50] | Government of Kenya (GOK). Kenya Rural Household Survey Report. Nairobi: Ministry of Planning, 2019. |

| [51] | Mwangi, J., & Wambugu, S. Farmer experience and dairy productivity in Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2022. 10(3): 145-156. |

| [52] | Njuki, J., & Sanginga, P. C. Gender and Livestock: Livestock and Women’s Livelihoods in Africa. London: Routledge, 2013. |

| [53] | Kristjanson, P., et al. Livestock ownership and gender patterns in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 2014. 64: 1-12. |

| [54] | Makokha, S., et al. Household structures and dairy farming in Kenya. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal, 2021. 87(2): 112-124. |

| [55] | UNESCO. Education and Literacy in Kenya: Country Report. Paris: UNESCO, 2020. |

| [56] | Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. |

| [57] | IFAD. Kenya Country Strategic Opportunities Programme. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2021. |

| [58] | Nanyeenya, W., et al. Adoption of artificial insemination in Tororo District, Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2020. 15(7): 945-953. |

| [59] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Livestock breeding and AI uptake in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 2021. 25(2): 33-44. |

| [60] | Kurwijila, L. R. Vaccination service adoption in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2021. 20(1): 55-67. |

| [61] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Livestock vaccination coverage in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 2021. 25(2): 33-44. |

| [62] | Katongole, C., et al. Deworming adoption in Bushenyi District, Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2020. 21(2): 112-124. |

| [63] | Gebremedhin, B., et al. Deworming service uptake in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Animal Production, 2020. 21(1): 67-78. |

| [64] | Kanyima, B. M., et al. Curative veterinary services in Mbarara District, Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2020. 21(2): 112-124. |

| [65] | Smallholder Dairy Farming in Tanzania. Outlook on Agriculture (2011). |

| [66] | Nanyeenya, W., et al. Mechanization in Tororo District, Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2020. 15(7): 945-953. |

| [67] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Milk cooling adoption in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 2021. 25(2): 33-44. |

| [68] | Ayuko, B., et al. Fodder adoption in Oromia Region, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2023. 18(3): 134-144. |

| [69] | Gichuki, S., et al. Pasture and feed adoption among Kenyan small-scale. Tropical Grasslands, 2022. 10(2): 45-56. |

| [70] | Katongole, C., et al. Silage adoption in Bushenyi District, Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2020. 21(2): 112-124. |

| [71] | Njuki, J., et al. Improved dairy breed adoption in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. World Development, 2020. 135: 105045. |

| [72] | Nanyeenya, W., et al. Improved breed adoption in Tororo District, Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2020. 15(7): 945-953. |

| [73] | Katongole, C., et al. Digital extension adoption in Tororo District, Uganda. ICT in Agriculture Journal, 2021. 5(2): 89-102. |

| [74] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Pregnancy diagnosis adoption in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 2021. 25(2): 33-44. |

| [75] | IFAD. Technology dissemination and dairy productivity in Africa. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2021. |

| [76] | AU-IBAR. Policy support for livestock technology adoption in Africa. Nairobi: African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources, 2022. |

| [77] | Bebe, B. O., et al. Small-scale dairy productivity in Bomet, Nakuru, and Nyeri Counties, Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2021. 9(2): 112-124. |

| [78] | USDA. Dairy Production and Consumption in the United States. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, 2020. |

| [79] | European Commission. EU Dairy Sector Report 2020. Brussels: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, 2020. |

| [80] | Israeli Dairy Board. Annual Report on Dairy Production in Israel. Tel Aviv: Israeli Dairy Board, 2021. |

| [81] | FAO. Global Dairy Production Statistics. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020. |

| [82] | Mwangi, J., & Wambugu, S. Feeding regimes and dairy productivity in Kenya. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal, 2021. 87(3): 145-156. |

| [83] | Gitao, C. G., et al. Veterinary service access and dairy productivity in Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2020. 52(6): 345-356. |

| [84] | Karanja, S., et al. Dairy productivity in Murang’a County, Kenya. Kenya Journal of Animal Science, 2021. 12(1): 67-74. |

| [85] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Dairy cow productivity in Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Animal Production, 2020. 21(2): 89-97. |

| [86] | Katongole, C., et al. Dairy yields in Tororo and Mbarara Districts, Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2021. 22(1): 101-115. |

| [87] | IFAD. Improving Dairy Productivity in East Africa. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2021. |

| [88] | World Bank. Agricultural Productivity and Technology Adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020. |

| [89] | Dohoo, I. R., Martin, W., & Stryhn, H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. 2nd ed. Charlottetown: VER Inc., 2010. |

| [90] | Githinji, J., et al. Deworming and dairy productivity in Nyeri County, Kenya. Kenya Journal of Animal Science, 2021. 13(2): 77-85. |

| [91] | Mwangi, P., et al. Deworming interventions in Mukurweini, Kenya. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal, 2020. 86(1): 55-63. |

| [92] | Sanchez, J., et al. Impact of parasite control on dairy productivity. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 2004. 62(2): 123-132. |

| [93] | VanLeeuwen, J., et al. Effects of deworming on dairy cattle health and milk yield. Canadian Veterinary Journal, 2006. 47(9): 882-888. |

| [94] | Thornton, P. K. Forage quality and livestock productivity. Agricultural Systems, 2010. 103(9): 573-579. |

| [95] | Karanja, S., et al. Improved fodder adoption in Murang’a County, Kenya. Kenya Journal of Animal Science, 2021. 12(2): 89-97. |

| [96] | Adebayo, O., et al. Improved forage adoption in Osun State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production, 2019. 46(1): 33-42. |

| [97] | Mupeta, B., et al. Fodder innovation in Rusitu Valley, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Journal of Agricultural Research, 2020. 58(3): 211-223. |

| [98] | Mekonnen, T., et al. Improved pasture adoption in Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Animal Production, 2021. 21(2): 99-108. |

| [99] | Wambugu, S., et al. Silage and hay feeding in Kenya’s Southwestern region. East African Dairy Journal, 2020. 15(1): 45-56. |

| [100] | Katongole, C., et al. Silage feeding and milk yield in Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2021. 22(2): 145-156. |

| [101] | Van Vuuren, A. M., et al. Silage feeding in the Netherlands. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2015. 212: 25-36. |

| [102] | Smith, J., et al. Silage feeding and dairy productivity in Texas, USA. Journal of Dairy Science, 2018. 101(4): 3567-3578. |

| [103] | Berisha, B., et al. Silage adoption and profitability in Kosovo. Balkan Journal of Animal Science, 2019. 7(2): 88-97. |

| [104] | Rege, J. E. O., et al. Crossbreeding strategies for dairy cattle in the tropics. World Animal Review, 2001. 72: 47-56. |

| [105] | Chagunda, M. G. G., et al. Performance of crossbred dairy cattle in Malawi. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2010. 42(8): 1617-1624. |

| [106] | Chagunda, M. G. G., et al. Dairy breed adoption in Tanzania. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 2012. 24(3): 55-64. |

| [107] | Chagunda, M. G. G., et al. Comparative dairy breed performance in Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2015. 10(12): 1456-1465. |

| [108] | Haggblade, S., & Hazell, P. Agricultural Development and Sustainability in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, 2010. |

| [109] | IFAD. Promoting Dairy Technology Adoption for Sustainable Livelihoods in Africa. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2022. |

APA Style

Chelanga, R. K., Ng’eno, E. K., Omega, J. A. (2026). Technological Determinants of Dairy Cow Milk Production Among Small-Scale Farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, Kenya. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 11(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11

ACS Style

Chelanga, R. K.; Ng’eno, E. K.; Omega, J. A. Technological Determinants of Dairy Cow Milk Production Among Small-Scale Farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, Kenya. Int. J. Agric. Econ. 2026, 11(1), 1-15. doi: 10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11

@article{10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11,

author = {Richard Kaino Chelanga and Elijah Kiplangat Ng’eno and Joseph Amesa Omega},

title = {Technological Determinants of Dairy Cow Milk Production Among Small-Scale Farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, Kenya},

journal = {International Journal of Agricultural Economics},

volume = {11},

number = {1},

pages = {1-15},

doi = {10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11},

url = {https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11},

eprint = {https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.ijae.20261101.11},

abstract = {Small-scale dairy farming plays a critical role in food security, rural livelihoods, and nutritional improvement in many developing economies. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the dairy sector is predominantly smallholder-based; however, productivity remains persistently low due to limited adoption of modern dairy production technologies and inadequate access to support services. In Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, small-scale dairy farmers continue to experience low milk yields per cow and per household, threatening household incomes, food security, and the sustainability of the local dairy value chain. Identifying context-specific technological constraints is therefore essential for designing effective policy and extension interventions. This study examined the technological factors influencing dairy cow milk production among 196 small-scale dairy farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County. A cross-sectional survey design was employed, and primary data were collected using structured questionnaires administered to farm households. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to assess the level of adoption of dairy production technologies and multiple linear regression to estimate the effects of selected technological variables on milk production. The results revealed generally low adoption of key dairy technologies. Only 42.9% of farmers used artificial insemination, 28% accessed deworming services, 26% accessed vaccination services, 17.3% adopted high-yielding fodder and pasture, and 21.4% kept improved dairy breeds. Average annual milk production per household was 2,925 liters, while average milk production per cow was 975 liters per year, equivalent to 4.5 liters per cow per day, values that are substantially below the national benchmark of approximately 10 liters per cow per day. Multiple linear regression analysis indicated that use of artificial insemination, access to deworming services, adoption of high-yielding fodder and pasture, access to improved feeds such as hay and silage, and adoption of improved dairy breeds had positive and statistically significant effects on milk production. Other technologies, including mechanized milking, milk cooling facilities, and digital platforms, did not show significant effects, largely due to their very low adoption levels among farmers. The findings demonstrate that technological adoption is a critical determinant of milk productivity among small-scale dairy farmers. Addressing existing technological gaps through affordable breeding services, improved animal health management, enhanced feed systems, and strengthened extension support is essential for increasing milk production, improving household incomes, and contributing to Kenya’s broader food security and agricultural transformation goals.},

year = {2026}

}

TY - JOUR T1 - Technological Determinants of Dairy Cow Milk Production Among Small-Scale Farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, Kenya AU - Richard Kaino Chelanga AU - Elijah Kiplangat Ng’eno AU - Joseph Amesa Omega Y1 - 2026/01/20 PY - 2026 N1 - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11 DO - 10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11 T2 - International Journal of Agricultural Economics JF - International Journal of Agricultural Economics JO - International Journal of Agricultural Economics SP - 1 EP - 15 PB - Science Publishing Group SN - 2575-3843 UR - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20261101.11 AB - Small-scale dairy farming plays a critical role in food security, rural livelihoods, and nutritional improvement in many developing economies. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the dairy sector is predominantly smallholder-based; however, productivity remains persistently low due to limited adoption of modern dairy production technologies and inadequate access to support services. In Marakwet East Sub-County, Elgeyo-Marakwet County, small-scale dairy farmers continue to experience low milk yields per cow and per household, threatening household incomes, food security, and the sustainability of the local dairy value chain. Identifying context-specific technological constraints is therefore essential for designing effective policy and extension interventions. This study examined the technological factors influencing dairy cow milk production among 196 small-scale dairy farmers in Marakwet East Sub-County. A cross-sectional survey design was employed, and primary data were collected using structured questionnaires administered to farm households. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to assess the level of adoption of dairy production technologies and multiple linear regression to estimate the effects of selected technological variables on milk production. The results revealed generally low adoption of key dairy technologies. Only 42.9% of farmers used artificial insemination, 28% accessed deworming services, 26% accessed vaccination services, 17.3% adopted high-yielding fodder and pasture, and 21.4% kept improved dairy breeds. Average annual milk production per household was 2,925 liters, while average milk production per cow was 975 liters per year, equivalent to 4.5 liters per cow per day, values that are substantially below the national benchmark of approximately 10 liters per cow per day. Multiple linear regression analysis indicated that use of artificial insemination, access to deworming services, adoption of high-yielding fodder and pasture, access to improved feeds such as hay and silage, and adoption of improved dairy breeds had positive and statistically significant effects on milk production. Other technologies, including mechanized milking, milk cooling facilities, and digital platforms, did not show significant effects, largely due to their very low adoption levels among farmers. The findings demonstrate that technological adoption is a critical determinant of milk productivity among small-scale dairy farmers. Addressing existing technological gaps through affordable breeding services, improved animal health management, enhanced feed systems, and strengthened extension support is essential for increasing milk production, improving household incomes, and contributing to Kenya’s broader food security and agricultural transformation goals. VL - 11 IS - 1 ER -